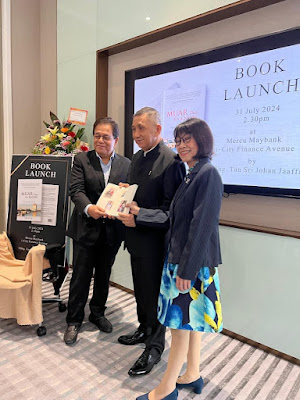

Media Integrity: Reflections of Upholding Truth, Transparency, and

Trust

Keynote Address

By Tan Johan Jaaffar

16th October 2024

International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation

(ISTEC),

International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM)

I must admit that this is one of the toughest topics ever assigned to me. I am supposed to talk about media integrity with reference to these key words – truth, transparency

and trust . But more importantly is the verb “to uphold” – upholding truth, transparency and trust.

In an imperfect world we are living in, truth, transparency and trust are virtues

that are fast dissipating, the discourse is therefore confined to these elegant

walls of ISTAC, no further, so to some

quarters it is almost ironical even talk

about it.

But we must.

In a world where distrust of almost everything – government, the

media, even the academia is overwhelming – it is about time to relook at

ourselves, to quote Shakespeare in Julius Ceaser, “for the eye sees not

itself, by reflections…”

We all know governments (all governments) are struggling to retain trust of citizens. That was the outcome

of a global survey spanning 40 countries. It revealed how government ministers

and officials are failing spectacularly to keep up with changes in the way

voters get information and form opinions. Weakened and distrusted central

government around the world have been incapable of responding to the Internet and

social media. Everyone in the position of power is being defied by social

media.

And there is also an issue

about the shifting dominance of social media platforms. At one time Facebook

was the supremo, the platform used by billions, so one can imagine the

influence. Then came Twitter (now X). A few years ago, TikTok took centre

stage. And as we learned in 2022, our own general election was largely decided by the power of TikTok especially among

Undi-18. The TikTokers ranged from social media savvy ustazs and ustazahs

to paid influencers that almost derailed the chances of Pakatan Harapan (PH) to

win.

Since one of the key words here is trust, let us look at

the world’s most and least trusted professions.

This graphic shows doctors, scientists and teachers are on the top

in terms of the world’s most and least trusted professions. One however must

take note that this was a 2021 survey, but I believe nothing much has changed.

The lowest on the chart are politicians

and government ministers.

Let’s take a look at Malaysia.

Yet gain, doctors are top,

followed by teachers, scientists, the armed forces personnel, judges, bankers

(bankers?), police and others. It is not

too far different from the global findings on the right.

But look at the top bottom of the chart. Lawyers, business

leaders, civil servants and journalists are at the bottom eight of the chart. At least politicians are three notches below journalists!

I am not trying to be apologetic here. We are not politicians. We

are not in the business of becoming popular. Or to appease anybody. Or to make

everyone feels good. We are

professionals first and last. We

acknowledged the fact that we have been

facing a cynical and sceptical public,

so the findings in the charts are not surprising. We have no issue with that.

We have been given all kind of names and labels. We have to live with it.

We are just doing our jobs. We are not taking advantage of other

people’s miseries or misfortunes. We do not want our names on the hall of fame just for exposing the

misdeeds of our political masters or the scandals of corrupt personalities. Or

the shenanigans and proclivities of entertainment personalities.

We don’t find pleasure in reporting what GISB Hildings have done

to children under their care or the fact that an aide of a former minister has

a “safe house” that is stashed with S$1.5 million. Or the divorce case of

Fattah and Fazura

We bring news to your living rooms. Real news, not fake ones. Not

deep fake. We trend on unfamiliar

and dangerous terrains. We encounter

dangerous people. We cover conflicts and wars. We play the role of the eyes and

ears of the people. We bring people’s stories to you. And the misdeeds of leaders: their transgressions,

corruption, nepotism, or to quote a familiar phrase from the Indonesians, their

cawe-cawe.

Journalists die in conflict areas bringing wars and skirmishes to readers, listeners and

viewers . Just remember how many of our brothers and sisters are killed or

injured in Palestine right now, and in Lebanon. Or in the Russia-Ukraine

conflict. Sometimes armies purposely

targeted journalists.

Just to give you an idea this

is the deadliest period for

journalists in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict since

1992 and the deadliest conflict for journalists in the 21st century.

As of September 2024, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 116 journalists were killed (111 Palestinian,

2 Israeli and 3 Lebanese) so far. A July 2024 count by the Gaza government

media office placed the number of Palestinian journalists killed at 160.

Anyone covering the Vietnam War, Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzegovina,

Rwanda, South Africa, Sudan, Somalia, Syria, Palestine and now Lebanon knew the risks.

I was in Afghanistan in the Spring of 1989, somewhere in the Kunar

province, not too far from Jalalabad covering the civil war there. I knew what

it was like. I experienced first hand the situation on the ground. The so

labelled rag-tag army (the Mujahiddins), never formally trained, who made up of

farmers and labourers, and ranging from age 14 to 80, fighting the second most

powerful army in the modern world. I knew why they won. I have seen them

battling the well-equipped Russian soldiers. Sadly after chasing away the

Russians they fought among themselves. And they still do. I was in

Bosnia-Herzegovina, South Africa, Somalia, Sri Lanka and other places.

It was not the adrenaline

that propelled us, nor was it fame and fortune. Again, we were just doing our

jobs. Don’t blame us for that.

Perhaps we are indeed doing a thankless job. But we are

professionals. We go to jail, we got hurt, some of us died. Occupational

hazards you may say. But we do what we are supposed to do. Forget about the

notion of the romance of journalism or the movies you watched about brave

journalists covering wars and coming back to their love ones. Happy ending

guaranteed despite the odds and challenges.

Journalism is more than that.

I have my fair share of adventures meeting some of the most

interesting personalities the world have ever known. Some of them even labelled

as terrorists, not just terrorists but one of them is the most wanted person by the Americans even this day. But they were

freedom fighters before.

I met Gulkbuddin Hekmateyar in the spring of 1989. He was leading

Hizbi Islami, the biggest and the most organised Afghan organisation back then.

He was fighting the Russians who invaded his

country in in 1979. Together with others like Ahmad Shah Massoud, better

known as the Lion of Panjshir Valley; Burhanuddin Rabani, the President of the

interim government of Afghanistan in exile and tribal lords like Abdul Rashid Dastum of Mazar-i-Sharif, they

gave the Russians and their puppet President, Najibullah a hard time.

They were hailed as heroes and epitomised in Hollywood movies. Remember the

character Rambo in the film where he fought alongside the Mujahiddins? “Beware

the venom of the cobra and the vengeance of the Afghans.”

It took the attack on New York in September 2001 and suddenly

every Mujahiddin in Afghanistan became a terrorist, Gulbuddin Hekmateyar included. What a

linguistic twist can do to a people and a nation. Ironically not one who were

allegedly involved in 9/11 incident was an Afghan.

Political leaderships almost everywhere in the world have not been

kind nor fair to journalists in most cases. Malaysia has a chequered history in

relation to journalists. Like me, many Utusan Melayu editors lost their

jobs. I wasn’t alone, joining the ranks of the late Tan Sri Zainuddin Maidin

and his predecessors, Tan Sri Mazlan Nordin and Tan Sri Melan Abdullah. We

carried that badge of honour in being fired as editors. Perhaps it’s true what

they say, that good soldiers don’t die, they fade away, whereas good editors

don’t fade away, they get fired.

I would like to believe that we were all collateral damage in the

grand political chess game involving some of the most refined and consummate

conspirators and political operators ever to roam the land.

Technically I “resigned” in July 1998, some three months before

Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim was fired on 2nd September 1998. They had

to “clean-up” the Utusan Melayu and Berita Harian groups and TV3

from “Anwar’s friends” in the media, as these were powerful platforms before

the advent of social media.

I was fortunate, my predecessor Said Zahari was incarcerated for

17 years. Another journalist, the legendary Tan Sri Samad Ismail was in prison

three times, twice under the British colonial rule. Sadly it was during the

reign of his fellow compatriots that he was in prison for five long years. The

country owes an apology to Said Zahari, Tan Sri Samad Ismail, Ishak Haji

Muhamad (Pak Sako) and many others for

placing them as enemies of the state. In actual fact enemies to some powerful personalities running

the state.

Now you have a better idea of what truth, transparency and trust

is all about. It is a matter of definition for the ruling elite. For us, those

are sacrosanct. We abide by those principles. We believe in those principles.

Let me give you a bit of context on the company that used to work

for back in the 90s. Utusan Melayu, the newspaper company was set up in 1939,

86 years ago to be exact. But what is

important to note is the role played by the jawi paper at the height of Malay

national consciousness and political awareness prior to and after Merdeka

(Independence). Utusan Melayu was an audacious daily that dared to take

risks. Utusan Melayu became a formidable force that was credible and

threatening to them.

Even after Merdeka, Utusan Melayu was a thorn in the

side of the Malay ruling elite who believed that Utusan Melayu was influenced by the “Leftists” (mereka

yang berfaham kiri). That was a good enough excuse for UMNO to wrestle

editorial control of Utusan Melayu in 1961. The journalists were up in

arms. Equipped with only determination and commitment, they fought back. They

launched a strike that lasted 90 days. They lost. As I have mentioned earlier Said

Zahari, the editor at the time, was taken under the Internal Security Act (ISA)

and was in jail for 17 years.

The way I see it, what happened in 1961 was a defining moment in

the history of newspapering in this country. Press freedom died at that moment,

never to be recovered, perhaps forever. The fiercely independent journalists of

Utusan Melayu paid dearly for their convictions.

Those are my reflections on how I position media integrity within

that context of upholding truth, transparency and trust. And this if even

tougher for me to talk about when the industry that I am in, for more than five

decades, are in a state of despair. Here I am sharing with you, an industry

that is bleak and with an uncertain future.

I

was crowned Tokoh Wartawan Negara by my peers in May 2018, presented in an

eventful and historic night organised by the Malaysia Press Institute (MPI).

While I was proud to be among a handful recipients over the years, all are or

were great names in the world of journalism. Legends all.

There is also another frequently asked question asked to veteran

journalists. Was I the “Hang Tuah” who

placed loyalty above all else. I can’t speak for others. But history will judge

me for what I did, for the exposès I made, for the leaders (including UMNO

leaders) who I held accountable for their actions. I lost my job eventually but that had been

due to the grand tussle involving the then Prime Minister, Tun Mahathir Mohamad

and his deputy, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim in 1998 (who is the current Prime Minister).

There are people who have been asking me, why talk about press

freedom when there is none? Is it true that the Malaysian press has been

kowtimed into believing that they have a role to play as “agents of change”

in the process of pembangunan (development) and kemajuan

(progress)? Are they being timid or

silenced into submission? Or were they merely unapologetic cheerleaders for

whoever was at the helm, now Pakatan Harapan, before that UMNO and Barisan

Nasional?

Those are relevant questions. We have been asking those questions

too as we went along. Were we complicit to some of the ills and injustices

inflicted upon individuals or even our society over the years? Were we merely

looking elsewhere when misdeeds became full-fledged scandals and these scandals

later became international disgrace? Sincerely we asked those questions too.

But to be honest, many of us tried our level best to ensure we

played the roles as expected of us. We did our best under such circumstances.

There were times when we were not proud of what we did. But we believed we had

tried our level best.

We made mistakes too. We are not supposed to take sides, but we

did. In one of my pieces for The Star (1st October 2018) I

asked the question that everyone of us ought to be asking: Are we complicit in

the 1MDB scandal? “Why did most of us fail to voice out concerns when the 1MDB

scandal was unfolding?”

My contention was that, too many people, including the mainstream

media contributed to the problem by ignoring the red flags and choosing not to

question the official line.

In my piece I wrote:

1MDB is a slap on the face of a cowering media.

1MDB is a wake up call for the local media.

Docility sucks.

Never again, that should happen. We must learn something from what

happened in those years leading up the full-fledged expose by Sarawak Report

and other news portals.

The truth is, there is no ultimate press freedom anywhere in the

world. Even in the US, the so-labelled liberal press is being pitted against

the conservative ones – it is like The Rest vs Fox News or The Rest vs

President Donald Trump. Someone famously said, freedom of the press belongs

only to those who own it.

Yet the war of attrition against journalists is getting new

traction. If Donald Trump wins the presidency again (which I am not surprised)

journalists are in for a more troubling

times.

The United States of America is supposed to be a beacon of

democracy and free press. Trump has called “the fake news media” enemy of the

people. Trump’s rhetoric is dangerous for it incites more than just distrust

and hatred towards the media.

Newspapers have been dying in slow-motion for a decade or so

already, some would argue. There is no future in the newspaper business. It

can’t be saved, even with the best of intentions. Media companies are facing

losses. I am not talking about only Utusan Melayu; even the mighty Media Prima

group, the Star Publications and Astro

are facing difficulties.

Even Malaysiakini, the loudest voice of reason online is having

problems.

We have to accept the fact that the newspaper is more than just

about the enterprise of newspapering. It is not only about the conversation on

raucous chauvinism or unapologetic political correctness. Or about sex, lies

and democracy, the three things that sell newspapers, they say.

It is also about quality, not just what the readers want. It is

about our responsibility to do our best as journalists. It is about the role of

the Fourth Estate. It is about accountability and fairness.

And about bringing sanity to a reading public that is obsessed

with film stars, celebrities and more film stars and celebrities. It is about

not relegating ourselves to prurient journalism fixated with telling the

official truth and avoiding dubious journalistic methods.

We need to recognise the important fact that newspapers and the

media as a whole are, first and foremost, business ventures. They are about

money. About resources. About profit. About the bottom line. Why would quality

newspapers fold? Why is it that even notoriously explicit and salaciously

sensational papers are suffering?

Back then, editors were reminded of a famous but anonymous 19th

Century verse about Fleet Street:

Tickle the public, make ‘em grin

The more you tickle, the more you’ll win

Teach the public, you’ll never get rich

You’ll live like a beggar and die in the ditch.

We were not just editors. We learned fast to make adaptations. We

made money for our companies. Our companies prospered. Back then, when I was at

the helm of Utusan Melayu, the total advertisement spending for Malaysia

was about RM3.5 billion, 60 per cent of that was for the newspapers, the rest

for TV. People advertised in our papers. Our papers were influential and a

money-making venture.

That was before the Internet, before the whole enterprise of

digital revolution disrupted our business. In fact we labelled the onslaught as

“disruptive technologies” with a hint of sarcasm. We thought we were formidable. Many of the

newspaper companies in Malaysia were forging ahead with lots of confidence into

the digital world in the early 1990s. We thought technology would propel us to

greater heights.

It did, at least for a while.

I have seen it all, from typewriters to old-styled newsroom and

the old printing machines. Later the newsroom became fully computerised. Back then

the Internet was still in its infancy. Gone were the days when reporters were

calling from phone booths and the layout of pages was done manually. We were

excited. Handphones came, then short message system or SMS. WhatsApp, Twitter and

Instagram were a decade away. The digital revolution was a sure thing, but for

us, we sincerely believed that it would help us more than it would disrupt,

destruct or even deconstruct us.

How wrong we were. We were literally caught with our pants down.

What we once believed as “unthinkable” became “inevitable”. It affected us, our

business, the entire discipline of journalism and perhaps the future of the

newspaper and media. Journalism was being hollowed out by massive structural

shifts, readers’ preferences, latest trends and the cost of the newspaper

business.

To say that all newspaper companies are affected is an

understatement. There are naysayers who believe that in the next five years,

almost all newspapers in the world will cease to exist in their traditional

form. The tide can’t be changed. The die is cast. It is just a matter of time.

If at all, the end is to be delayed, not halted.

Then companies in Malaysia and elsewhere are shifting their ad

spend to social media and digital platforms. Media companies have a lot to

complain about the Big Four - Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google. They have

every reason to be unhappy. Many believed that these companies are the new

imperialists of the Internet era. They are the new colonisers of today’s world.

Their imperial ambitions know no bounds, some argue.

There is a raging debate

out there on how “harmful” the powers

are in the hands of these tech titans.

There are arguments about how online platforms have used their power in

destructive and harmful way in order to expand.

They carry our news, but they don’t pay. In fact they make money

from our hard work. That isn’t fair.

But we have to accept the reality that news business

is not the exclusive right of media companies. Anyone can be a reporter.

Backpack journalism is the in-thing, whatever that means. But social media is

real time. A nasty road accident outside ISTAC now will be on YouTube real-time

or on any of the social media platforms. There is no need to wait for the news

bulletin update on Astro Awani or for TV3’s Buletin Utama at 8.00

pm tonight.

But is serious journalism

at stake?

But at least there are people out there who still believed that

the mainstream media remains the true main source of information, a platform

that must continue to be trusted. Datuk A. Kadir Jasin, a veteran newsman

himself and former editor of the New Straits Times, who was the media and communication adviser to the

Prime Minister Tun Mahathir Mohamad when he became PM the second time, argued

that the mainstream media industry comprised trained and licensed professionals

bounds by ethics and laws in their pursuit of true and verified information.

According to Kadir, “It differs from social media, which is not

news, but a social medium that can be used by anyone and everyone to say

whatever they want, just like in the coffeeshops.”

“So, we don’t have to get muddled with what social media offers,

as correct information can only be obtained from the newspapers, radio,

websites and television,” he said.

I am sure many would

disagree with Kadir. It is for us, comforting to hear that.

But we all agree that the Internet is a cowboy realm. No country

in the world can control social media. The advancement in telecommunication technology

has disrupted humanity in many ways – the way we communicate, govern,

education, family, you name it. Humans have been control of their creations

since the invention of the wheel. But not this one. We are losing control of

the Internet, the social media and all that is associated with it.

Digital technology is a monster unleash. Communication technology

today is heralded as the totem pole of freedom and free speech. Yes, we agree,

information must be free, unedited, uncensored, and available to all. But today

with digitalisation we are looking at a frightening new meaning of the word

freedom.

Social media can easily be a weapon of mass destruction.

Anyone can say anything. Anyone can spread lies. While it is a democratic tool

it is a scrouge when its misuse is rampant and irresponsible. The finger is mightier

dan a thumb drive which is mightier than the sword. Just look at the vitriol,

the hatred, the lies in the social media.

Little wonder misinformation is a huge global humanitarian crisis!

Fake news is the rule of the game.

The truth is, the social media revolution is changing everything.

Social media platforms care little about “truth”. Truth is elusive. Who

cares where we get our news from or whether such news are true or fake. The way

I look at it, the whole notion of “news” needs reviewing.

But there is also a silver lining. What the mainstream media can’t

do fast and effectively, the social media can.

Having said all that, do I still believe in freedom of the press?

An unequivocal yes for me. But freedom has its responsibilities.

Just take a look at Indonesia.

There are accusations that

the government of President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) is trying to curtail press

freedom and freedom of expression. The

truth is, Jokowi himself is being vilified by certain quarters of the media.

Accusation that he is creating a political dynasty is one of the hottest debates in the media

during the presidential election or pilihanraya presiden (pilpres) 2024)

in February this year.

Over the years Indonesia’s press

freedom is not something to be proud of.

In 2023, it is ranked 108 out of 180 countries according to Reporters

Without Borders (RSF). In 2021 Indonesia was in

113th position while in 2022 it drops to 117.

Within that scenario many people are

sceptical that the press will enjoy unrestricted freedom during pilpres 2024 and the coming regional and

district elections or pemilihan

kepala daerah (pilkada) and election

for governors or pemilihan umum gabenur (pilgup) in November.

One must remember the election this

time is not fought just on the airwaves and the print media but more so in

the social media. There is a new generation of Indonesians who are not familiar

at all with traditional media. These are the Generation Z and the millennials. According to

Indonesia’s statistics department, those born between 1997 and 2002 are the

dominant demographics in Indonesia today. There are currently 74.9 million of them or 27.9 per cent of the

population. At least 70 per cent of them have breached the voting age of 17

years old.

So one can imagine the power of this

group.

YouTube channels are providing the

space for open discussions. Every TV

station and major newspapers have its

own offerings on YouTube. On the airwaves TV stations are competing to get the attention

of viewers by putting up talk shows that are extremely opiniated,

even contentious and controversial.

There is always “the other side” to allow free flow of discussion by all sides

and pendukung (supporters).

Some of the talk show are

hugely popular and watched with interest

beyond the shores of Indonesia via YouTube and other social media platforms.

Some of the popular ones are Rosi, Panggung Demokrasi, Kontroversi, Q&A,

Mata Najwa, Catatan Demokrasi and Indonesia Lawyers Club. Even the former head

of Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (their anti-graft outfit), Abraham Samad has his own podcast, Abraham Samad

Speak Up. Another popular political podcaster is Hersubeno Arief on Forum News

Network (FNN). They are many others like them.

These talk shows and podcasts

are redefining the rules of engagement

for its openness. The debates are

mostly civil despite its ferocity and harshness. Indonesians are good at

laughing off heated debates.

I believe Indonesian society have

matured politically. I have seen a more robust press in a handful

of Asean countries when it comes to

election but Indonesia deserves full credit this time. While it is true that many politicians and

oligarchs are still owning media

organisations in the country but as the whole, the press is free and open.

For me, the true winner of this pemilu is the free press.

We need probably another 10 years to reach that level.

And then there is the Fufufafa debacle. It was an old online postings that appeared on an online forum, “Kaskus”. Kaskus was created in November 1999 as an informal forum for Indonesians students

abroad. It later evolved into the

country’s best, largest and the most

popular online community.

There was an account registered as “Fufufafa” in Kaskus. Just like

any other accounts, Fufufafa was critical of certain individuals, making fun of

others, explicitly showing adoration of certain celebrities, at time even funny

and mentioning body parts of certain female artistes, and linked to sensitive

content like pornographic site sign-ups. The

owner of the account sounds conceited, crass, disrespectful, even

brutal. He is also a misogynist, racist

and sexist.

But the account comes to haunt the person 10 years later in a shocking and dramatic way. This account is

the biggest single Internet debacle in the history of Indonesia.

This is the case allegedly involving the deputy president-elect, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the eldest son of

President Joko Widodo (Jokowi). He is to be sworn in office on October 20th after winning the

presidential election partnering Prabowo Subianto. The account is sadly redefining a

presidential partnership in Indonesia.

So, why is the postings of a 26-year old at the time matters

now? For one, he is to be the next vice

president of the Republic of Indonesia. There is an issue of integrity,

conduct and behaviour of a leader.

Gibran is the second most powerful person in Indonesia on October 20th.

If anything happened to the 72-year old Prabowo, Gibran is the next president.

But what about the future?

It is time that media practitioners look hard and deep into

themselves. Things are changing. Media practitioners need to make adjustments.

And adaptations. Or they will perish.

But for me, the most important thing to ensure that a free and

responsible press is the pillar of a vibrant, working democracy. I applaud the

government of Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak to designate a date as

National Journalists’ Day or Hari Wartawan Negara (Hawana). The date

chosen is May 29th, the day

Utusan Melayu was born in 1939.

Hawana is about the nation’s recognition of the role of journalists as a

whole. They are the unsung heroes in the

country’s narratives.

Nothing has changed regarding the need for independence of

journalists working anywhere in the world today, especially in developing

countries. But Indonesia has shown how a free and vibrant media is playing a

positive role in nation building.

And yes, freedom of the press must come with responsibility. So it

is incumbent upon the journalists fraternity to prove its worth. Politicians

come and go, journalists stay. That has been my advice to the younger

generation of journalists. They are

judged by their adherence to the code of ethics and the acceptable standard of

accountability that is expected of them. Not by their loyalty to the

political masters. The demand for fairness and independence is louder now

than ever before.

I understand the love-hate relationship or the hate-hate

relationship between the press and the public and the press and the ruling

elite. No one really like us – politicians, the business tycoons, the

oligarchs, and more so the corrupt and the crooked politicians,

technocrats and businessmen and women.

But my brothers and sisters in the press will strengthen their

resolve to play the critical role in society. But more importantly the

government of the day must allow us to

work under a conducive atmosphere without fear and favour. They must review,

repeal an abolish archaic laws that have lost its relevance.

The last thing we expect is the freedom and the independence of

the press to be trampled in anyway for various political needs, through laws

that will stifle the journalists and the state apparatuses to control free

press.

Only then, an unrepentant orang surat khabar lama like

me believe, that media integrity will be

achieved and truth, transparency and

trust can be uphold.

Thank you.