“THESE

ARE MY PLAYS” By JOHAN JAAFFAR

The

Institut Terjemahan Buku Negara (ITBM) published the English translation of

Johan Jaaffar’s seven stage plays. The plays were translated by Professor Dr.

Solehah Ishak. The Bahasa Malaysia edition was published by Balang Rimbun Sdn

Bhd in 2012

The original plays in BM published by Balang Rimbun Sdn Bhd

An anthology of Johan's plays published by DBP in 1981

Introduction

to Johan Jaaffar’s plays:

Johan

Jaaffar’s Alterities

The

early school years:

Reading Johan Jaaffar’s plays and seeing his theatre

productions would give readers/audiences the opportunity to delve into the many

continuums of this “third generation” Malay playwright, the generation after

the bangsawan, sandiwara and the

realistic sitting room plays of the drama

moden period. Johan Jaaffar is a playwright belonging to the Malay

absurd-abstract- “absurd-ala-Malaysia”- surrealist, experimental decade of the

1970’s. Although the playwright’s mark of dramatic activity and creativity

emerged in the 1970’s, Johan was already actively involved in drama activities

even as a young primary school student, at the Sekolah Rendah Perserian

Semerah, Johor in the early 1960’s. Then he not only watched sandiwara plays but helped whenever he

could or was needed. This continued into secondary and later his high school

years at the Sekolah Tinggi Muar where

Johan would be in charge of writing scripts, choosing the actors and was

responsible for directing the school’s dramatic presentation. In these early

years Johan derived his ideas and inspirations from Malay literary canons like

the Sejarah Melayu/ The Malay Annals

and the Hikayat Hang Tuah amongst

others.

The

university years:

As an undergraduate at the University of Malaya from

1974-1977, Johan Jaaffar became even more actively involved in the writing and

production of plays. He was an active member of KESUMA (Kumpulan Kesenian

University Malaya), the Cultural Group of University Malaya. In 1965, KESUMA

staged Johan’s “Kotaku Oh Kotaku”/(“My City Oh My City”) at the University’s Experimental

Theatre. Johan not only wrote the script but was responsible for directing the

theatre production. Again in 1976, KESUMA staged yet another of Johan’s play, Angin Kering/Dry Wind, again at the same

venue.

As an undergraduate at the University of Malaya from

1974-1977, Johan Jaaffar became even more actively involved in the writing and

production of plays. He was an active member of KESUMA (Kumpulan Kesenian

University Malaya), the Cultural Group of University Malaya. In 1965, KESUMA

staged Johan’s “Kotaku Oh Kotaku”/(“My City Oh My City”) at the University’s Experimental

Theatre. Johan not only wrote the script but was responsible for directing the

theatre production. Again in 1976, KESUMA staged yet another of Johan’s play, Angin Kering/Dry Wind, again at the same

venue.

Johan Jaaffar, Dinsman, Hatta Azad Khan together with a few

other theatre people, form the Third Generation of Malay Theatre activists.

This Third Generation started their theatre activities in the university

campus, especially in the post May 13, 1969 decade, a date noted for the racial

riots which sundered the nation. The racial riots led to the introduction of

the New Economic Policy and also the Rukun Negara (National Principles) amongst

others. It is within this decade of turmoils, uncertainties, of racial harmony

gone awry, that this Third Generation of playwrights experimented with the

absurd, avant-garde plays. Johan wrote Angin Kering,

Dia and Sang Puteri, his trilogy of absurd/ experimental plays. The Third

Generation Playwrights deliberately left behind the familiar, realistic sitting

room plays of the 1960’s.

It was also a post May 13, 1969 decade marked by the

pioneering play of Bukan Lalang ditiup

Angin, written by Noordin Hassan as a signifier of May 13, 1969 with

various signifiers aimed primarily at his Malay readers/audience. The experimental

decade of the 1970’s was marked also by Dinsman’s Bukan Bunuh Diri/”Tis Not Suicide” (1974), and Hatta Azad Khan’s

“Mayat”/”Corpse” (1976). This Third Generation of playwrights not only

experimented with the craft of playwrighting but also in the choice of

“stories” told or untold. They dared to experiment with the aim of exposing

their society to be scrutinized. They were also a group of highly educated

dramatists, exposed to and perhaps influenced by western writers.

The

working years

Johan’s foray into “official” employment was at the Dewan

Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP). It is not my intention to delineate Johan’s career

path but it is important to note that at DBP, Johan was surrounded by other

literary figures, or important columnists, who helped spurred the growth and

shaped the Malay literary scene. These include the influential columnist of the

1970’s-1980’s Datuk Mohd. Noor Azam and writers like Baha Zain, Anwar

Ridhwan, Dinsman, Sutung R.S. and Othman

Haji Zainuddin amongst others. Johan was

also close to Malay writers of the older generation like Keris Mas, Usman

Awang, Pak Sako, Arena Wati, Samad Said and Abdullah Hussein.

At DBP, Johan also had the then auditorium of Balai Budaya

(now the BalaiTun Syed Nasir) at his disposal. It was here that Johan continued

to hone and develop his theater making activities. Besides the writers and the

readily available auditorium at DBP, Johan was also deeply engaged with a group

of theatre performance arts practitioners at Anak Alam, comprising a group of

writers and artists who declared about their innate freedom to be creative and

experimental. These include Malaysia’s renowned artist Latiff Mohiddin, other

writers-poets-performers like Mustafa Haji Ibrahim, Ghafar Ibrahim, Khalid Salleh, Muhammad Abdullah and Pyan Habib.

Based on their guiding principle of their innate freedom to

create and experiment, members of Anak Alam, produced absurd plays, voicing

their anger, protests and anti-establishment attitudes. Johan Jaaffar could be

said to have met his artistic spaces and inter-spaces under the roof of Anak

Alam, whose hallmark had been the need and the right to produce creative,

experimental works as they deemed fit.

As stated earlier, this introduction is not concerned with

the trajectories of Johan Jaaffar’s various careers. They are mentioned only to

situate him as an important playwright.

Johan has moved from DBP to work as Chief Editor of the Utusan Group

of Publishers, became in his own

words a farmer for a while to now head one of Malaysia’s paramount multi-media

agency, the Media Group of Companies.

Johan

Jaaffar: The ever present playwright:

Undeniably Johan Jaaffar, grew up, worked in, was exposed

to, loved and was sometimes exasperated by Malay theatre. Unfortunately for

Modern Malay theatre too, Johan Jaaffar has not been as prolific as his theatre attending or script reading public would have liked for reasons best known to

him alone, besides of course his monumental work commitments. Still it cannot

be denied that Johan’s involvement with theatre is manifold. He not only write

scripts, he also direct scripts, both his own and that of others. It is also a

testimony of his talents that he has also acted in these theatre productions.

Johan can be labeled as a playwright-director-actor in the mould of the late

Syed Alwi. More than that Johan is also an insightful and sharp critic not only

of theatre but of his social-cultural-political-economic milieux.

In the field of theatre, Johan not only write plays for the

stage but he was also involved in radio and television plays. The television

plays produced in the 1980’s include “Asy Syura”, “Angin Bila Menderu”, “Pak

Tua”, “Pendekar Raibah” and “Pemain”. Besides writing original scripts for

television, Johan also adapted novels both for the stage and for television.

These include the novels of Anwar Ridhwan like Hari-hari Terakhir Seorang Seniman, A. Samad Ismail’s short story

“Rumah Kedai di Jalan Seladang”, A. Samad Said’s Langit Petang, which became Langit

Petang: 12 Tahun Kemudian. These plays were televised by RTM, the Radio and

Television Malaysia network. Another of A. Samad Said’s novel which was adapted

by Johan Jaaffar for the stage was Salina.

It has been said that Johan read the novel thirty times before he adapted the

novel for the stage. Such is Johan’s determined gregariousness and devotion not

only to details but to get to the deeper resonances of the text so as to

successfully translate and transform it into theatre.

A charismatic figure, a sharp critic, and an avid theatre

practitioner and goer, the ever present playwright, Johan’s aura, and influence

is far reaching. His Angin Kering and

Kotaku Oh Kotaku have been produced

numerous times even as they continue to beckon new directings and new readings.

Veteran as well as up and coming theatre groups continue to be fascinated by

Johan’s plays. It is not surprising that Johan continues to play a mentoring

role to theatre activists, both small and great.

READING

THE PLAYS

1. ANGIN KERING / DRY WIND

Angin Kering was staged at USM in 1979

“Angin Kering”/“Dry Wind”

is the first play in Johan Jaaffar’s trilogy in which he posits

characters ranging from the all knowing, Mahatahu, to the all wealthy,

Mahakaya, and his wife at one end of the social-economic spectrum and the

ordinary paddy planters and their families at the other end of the spectrum.

Mahakaya and his wife live in a luxurious mansion which is cooled by powerful

air-conditioners, where the temperature of their bath water is constantly

regulated to be coolest in the midday and warmest in the cool night. They have

a Slave who has a daily chore of 99 things that he must do to please his

master. Slave is constantly reminded that he is the twenty-second slave to have

been employed by Mahakaya. All the other former twenty-one slaves having been

cursorily dismissed for not doing their jobs well.

Yet

another important character is Si Jelita, the Beautiful one whose voice is

melodious and who sings of reasons in an age or in a society where reason is

absent. Beautiful, perched high on a boulder, can see the dichotomy of life in

the play’s milieu. Beautiful is surprised at so much wealth on one side of

society and such dismal poverty on the other side of society. This economic

divide is sundered by searing heat where the sun has scorched the farming

society and terrain with only the dry winds blowing. On the other side of

society, where the wealthy live there is the danger of a deluge of

uncontrollable flood water about to destroy the palatial homes and

surroundings.

Mahakaya has ordered Slave to demolish the dam so that the

rising flood waters will not proceed to drown their property. But Slave also

knows that demolishing the dam will not only arrest the flood waters, it will

also cause destruction and death to the paddy farmers and their land. More

importantly, he knows that amongst these paddy planters are his parents.

Demolishing the dam means that he would also be directly responsible for the

deaths of his parents. Understandably, Slave refuses to do what his master, the

Mahakaya, has ordered him to do.

Slave returns to his village to be welcomed by his parents

like the proverbial return of the prodigal son. They honour him with titles befitting, in their minds and

imagined beliefs, their wealthy status in life, where their huts are

miraculously transformed into mansions, where food abound and there is much

merry making. But Slave knows that he has returned home not bringing honours,

respect and wealth but death, defeat and annihilation not only to his family

but to the whole farming community. Still the paddy farmers are deluded by the

very poverty which they seem to think as abundant wealth, the scorching heat

which they seem to feel as the cool breeze, dust and dirt which they regard as

comfort.

The paddy farmers are on a binge of eating, merry making

and generally enjoying themselves luxuriating in abundant wealth, food and

laughter. Beautiful with her sweet voice, pretty face, attractive demeanor sees

the truth of the reality. She cannot understand the joyous merry making

accompanied by loud music and the general commotion of celebration. She does

not see that there is anything to celebrate or be joyful about for the paddy

farmers are only deluding themselves. What they see as cool, beautiful weather

is scorching, unbearable heat and what they see as a feast of good food is the

devouring of their own flesh.

The farmers realize that in the midst of this wealth where

their barns are full of rice, they must still fight the onslaught of natural

enemies. Reminiscent of Shahnon Ahmad’s No

Harvest but a Thorn, where Lahuma had to fight all manner of insects, birds

and prey to defend his paddyfields, likewise in “Angin Kering” Patani, Matani

and the other paddy planters had to safeguard their rice land from the rats,

snakes, crabs, the tiak birds and

other disasters coming their way. Patani in his delusory hallucinations “dream”

of living in a house where the furniture are all imported from abroad,

including from Switzerland, carpets from Afghanistan, chandeliers from Austria.

Even the building materials are imported from overseas, like bricks from

Taiwan. His house/mansion must have glass walls with a dome and decorated with

original paintings by Michaelangelo, Renoir and Picasso.

Beautiful, too, has her own dream as she herself admitted.

She dreamt of living in a huge, beautiful house where she will live comfortably

and luxuriously with servants to entertain her every need, whim and fancy;

moreover she will be able to eat whatever she wants and all the delicacies she

desires. More than that, she will adorn her body with gold and diamonds and in

so doing further enhance her beauty.

In “Angin Kering” the playwright has constructed an

oppositional binary of drought and flood, dry wind and wet wind, of absolute

poverty and unbounded wealth. But in the end the playwright has also demonstrated

that wealth and the ability to enjoy wealth and bask in luxury with their every

whim catered to, is not the prerogative of the wealthy and mighty only. In this

play, even the poor farmers dream of untold wealth, unparalleled luxury and

boundless enjoyment and merry making. In their deluded minds, what they are

celebrating, enjoying and honouring are real and true. Perhaps by constructing

this trajectory, the play highlights the fact that man, no matter from which

end of the social ladder or spectrum they come from, share the same needs,

wants and dreams. They all want to be rich, live a life of luxury and bask in

all manner of comfort. In short, they want to live the good life.

Thus in this play, Slave sometimes talks like a poet. At

other times he sounds like a lawyer although in his common demeanor, he is a

mere slave doing all that his master, the All Wealthy Mahakaya bids him to do,

including demolishing the dam which will kill his parents.

The playwright also takes a jibe at the education system as

is revealed in the conversation between Mahakaya and his Slave as to why he did

not go to school. Slave’s father saw no point in having him formally educated,

for as Slave says, those who go to school are just like parrots. They do not

think, they only ape and repeat what others say and do.

“Angin Kering” is not only a powerful play of social

criticism but is also a play of justice and equality in terms of shared dreams,

wants and needs not only of the powerful wealthy, but also of the powerless poor.

Again, what unites the rich and the poor, like everyone else, is the common,

sure certainty of death, for as the character in the play states, everyone will

certainly die, although what is also a fact is that no one really wants to die.

Written in a language which is repetitive, short but very

impactful, the play does not use long dialogues to hammer home the message of

social (in)justice and (in)tolerance. Almost poetic in its staccato manner of

presenting dialogues, interspersed with the songs sung by Beautiful and also

the occasionally non-staccato lines of normal dialogues running to a few lines,

the play constructs a world of almost hallucinatory delusion and abject

reality.

2. DIA / SOMEONE

THROUGHOUT his play-writing career, Johan Jaaffar has been

concerned with investigating and delving into the bowels of his society so as

to better highlight the aberrations and anomalies that exist in his milieu,

with the hope that the exfoliation of such concerns will better that very

society. Thus it is that Johan’s plays are concerned with social and human

shortcomings, transgressions, iniquities and inequalities. Class differences,

exploitations, greed and untold sufferings are scrutinized and magnified by the

dramatist with the hope of changing and improving his environment. His

characters are therefore searchers who are always on a quest for social

justice, equality, and above all, a general improvement of their living

conditions.

“Someone” (Dia), the second play in Johan’s trilogy which

contains “The Dry Wind” (“Angin Kering”) and “The Princess” (Sang Puteri) are

peopled by characters who are on a quest for their personal “grail.” Si Pencari

(The Searcher/Seeker) seeks for someone--anyone or anything, that can give

meaning to his life and make it whole again. Si Kaya [The Rich One] who,

inspite of his wealth, is still a dissatisfied person. He too seeks for

someone. Tukangnya [His Craftsman/Aide] courts personal glory through the

creation of a magnificent golden dais which will be the ceremonial seat for the

someone which Si Kaya and Si Pencari pursue. The splendor of creating the dais,

combining, in Si Tukang’s words, both “engineering and technological feats” are

means of glorifying Si Tukang’s own creativity and prowess. Si Tukang seeks and

finds purpose in his life in a physical structure. Si Gadis Buta [The Blind

Girl] and Ibunya [Her Mother] on the other hand, are only after the basic

ingredients to enable them to live. They want nothing, only food, water,

shelter and clothing.

Johan’s “Someone” is a play where the characters are on a

mission where they seek for meaning in life. The play exemplifies the endeavors

undertaken by Si Pencari and Si Kaya, to find someone. Unlike Beckett’s

Vladamir and Estragon who waited for Godot, Johan’s Si Pencari and Si Kaya do

not know who or what they are looking for. It can be anyone, a he or a she, or

anything for that matter. Where Vladamir and Estragon failed to meet Godot, Si

Pencari succeeds in meeting his someone. But the someone is neither a leader, a messiah, a Mahdi, a fuhrer or a duce; she is but only a blind, starving girl, who is on her

personal quest to assuage her hunger. She only seeks for food and drink. Her

life would be significant and meaningful again if she can only have food.

It would seem, on a simple, textual level, that in

“Someone”, it is only Si Pencari who finally succeeds to find the someone. Significantly too, this someone

would be duly honoured and glorified. It is towards this purpose that Si Tukang

has crafted a magnificent golden dais, gathered an assembly of dignitaries,

arranged a ceremonial reception, and organized a carnival to celebrate that

someone’s coming. Even as “Someone” is concerned with the search to find

meaning and purpose in life, the playwright cannot resist poking fun at his

society which is still inundated with ceremonies and ceremonial functions. Thus

the welcoming committees, the golden dais, the honour guards and smiling

maidens, all of which testify to a community besotted with unnecessary

official, ceremonial rites and rituals.

Si Pencari’s faith transforms Si Gadis Buta into the

someone whom he has been waiting for all this while. Si Pencari will replace

her stinking rags for clothes of the finest material. Si Gadis Buta will be

washed, perfumed and adorned with the most precious and delicate of jewellery.

And lo and behold, Si Gadis Buta becomes not only a reincarnation of goddesses

of a bygone era, she indeed becomes the very someone whom Si Pencari seeks.

More importantly, just as Si Pencari’s

faith and belief have succeeded to realize all these transformations,

that very faith too has now endowed Si Gadis Buta with sight.

The Blind One can now miraculously see. But the sight in

front of her eyes is not something that she wants to see: a throng of people going

amok, deaths and bloodshed. Si Gadis Buta would rather be blind again so that

she would not have to see the scene in front of her. Throughout the honours

that are heaped on her, the basic thing that she yearns for is still beyond her

grasp. She remains hungry and she continues to starve.

The playwright does not only deny Si Gadis Buta the basic

ingredient of food, he also annihilates the novel experience of her gaining

sight. At the same time, Johan again mocks his society with its public

acclamations of helping the poor, the down-trodden and the neglected. Si Teman

derides the effort of the state to help the lower denizens of society. He

ridicules the public exposure involved when aid is to be rendered to the poor.

The grand publicity, with cameras zooming in on the cheques to be handed out,

is not proportionate to the actual aid doled out to the needy. Si Teman sneers

at the red-tape involved, the appointments to be made, the schedules to be

followed by those who beg for help and who do eventually get whatever meager

help from the welfare agencies.

Si Teman does not only scoff at such official rituals, he

is also the voice of reason who taunts Si Pencari. If Si Pencari deludes

himself into believing that someone does indeed exist, Si Teman ascertains that

the former knows that that someone is but a figment of his crazy imagination or

absolute yearning which has resulted in a hallucination of make-belief. For Si

Teman, the someone has yet to materialize. In fact he does not know what or who

that someone is. The playwright, through Si Teman, in fact denies any

possibility that Si Pencari’s mission is accomplished, or that he has found

what he has been seeking for.

In fact the subtext of “Someone” is instead complete

annihilation and destruction: Si Pencari’s

success and beliefs are destroyed by Si Teman’s reasons and rationality. Si

Gadis Buta’s transformation and sight are nullified by the reality that

confronts her and her failure to get the most basic of necessity like food to

stop her starvation. Si Kaya’s success in creating buildings and the

sky-scrappers which he built are ravaged to the ground because men decide to

fight men. The playwright does not only deny Si Kaya his social accomplishments

in the form of multi-million dollar buildings, he even refutes Si Kaya’s

physical ability by making him blind at the end of the play. Si Kaya finally

has nothing: no wealth, no dignity, no track record of his accomplishments and

worse of all, not even his own sight.

As for Ibunya [The Mother], she will continue to wait and

hope that something will happen to change and better her life. She has absolute

faith in her God and she believes that what she gets, what she is and what she

will become, are all in god’s hand. Her life is beyond her control. It is all fated

to be thus.

The playwright not only deprecates the ceremonial rituals

embedded in his society, he also denounces state efforts in eradicating poverty

and mocks at rituals as can be seen in Ibunya whose absolute pietism can only

ensure that she remains manacled in her poverty stricken life. “Someone”

exemplifies Johan’s absolute despair, anger and helplessness at his society for

although it is marked by rapid economic progress, nevertheless leaves the

majority of its subject poor, neglected, deprived and still striving for the

most basic of human amenities like food

and shelter.

The

playwright paints a bleak picture, denying any form of positivism for he wants

to confront his readers and audience with such a hopeless condition of human

society with the hope of jolting them into a new social consciousness and

awareness. The dramatist wants to liberate the members of his society from the

shackles that have fettered them for so long. In an “interview” with this

writer, Johan said that he was obsessed with writing “Someone”. He wrote

nonstop for several days. It was also written during a period of real

depression in 1976, marked by unemployment and the fact that Johan was at the

threshold of a new life, where he must decide to enter the labour force or stay

ensconced in the world of studies and academia.

Although it only took a few days to write and finish the

play, it was not performed for several years. In fact “Someone” had its stage

debut only in 1982. The playwright admitted that it was his most difficult play

to perform. Most of Johan’s plays are usually visualized on paper and then

produced on stage. With “Someone”, Johan was without any direction as to the

end product of a theatre. As he puts it, he “simply did not know how to stage

it.”

When he finally decided to direct “Someone” it was done on

a shoe-string budget, with a cast of completely new actors. It formed part of

the festival organized by a conglomeration of theatre groups called the “teater

generasi ke3” [the third generation of theatre people]. “Someone” itself was

staged by the Avante Garde Theatre group. Since Johan, the playwright-director

had no idea how he was going to produce “Someone”, he decided to produce the

play on a bare stage, without any sets or props to further enhance the desolation

that is the sub-text of “Someone”. The bare stage is also an appropriate symbol

of the nothingness, namely of having nothing, that forms the spine of the play.

The cast would also be an assembly of new actors.

Crew working to set up a set for one of Johan's plays

Since it’s first and only production in 1982, there have

been several requests to reproduce the play, but the dramatist has refused

permission, preferring to guard this play which he wrote “like a man obsessed”

to himself. Perhaps Johan’s possessiveness can be attributed to the anguish

which he felt at the chasm which splits his society into the super-rich Si Kaya

and the down-trodden, starving Si Gadis Buta and Ibunya. Whatever the

playwright’s reasons, his purpose in exposing such bleakness and despair in

“Someone” must surely be his realization and anger but yet

embedded within it is the hope

that his society can still be changed, and made better.

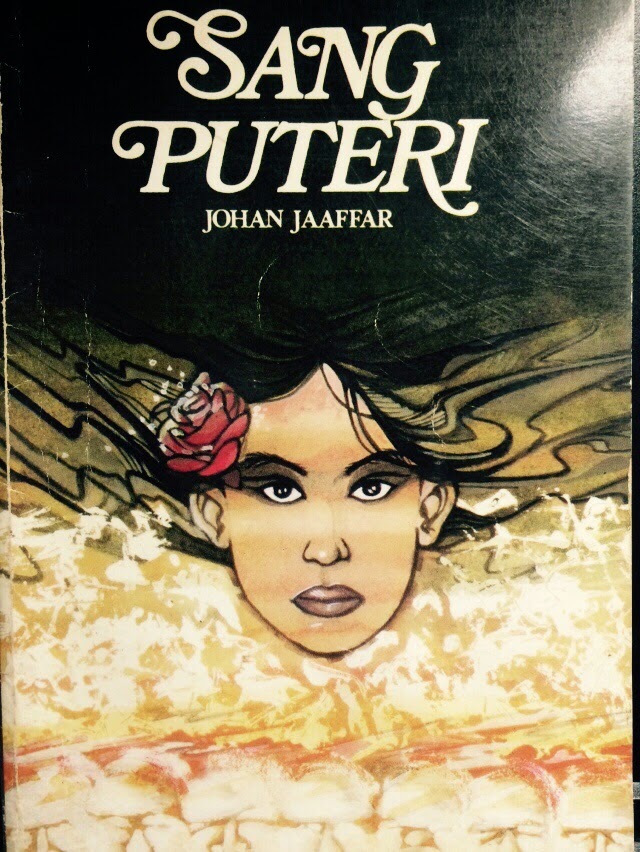

3. SANG PUTERI / THE PRINCESS

Sang Puteri was first published by Sarjana Enterprise in 1981

“Sang Puteri” (The Princess), the third play of Johan

Jaaffar’s trilogy posits characters who are again divided by the haves and have

nots. On one end of the scale are people like Anjang, Mak Anjang, their

daughter, Inah, her beloved Andak, the soothsayer and village elder, Tok Aki,

who lives by customs and traditions. On the other end of the spectrum are

Tuanda and his entourage of personal aides, headed by the Pamanda. Like all

rich people with power, Tuanda will never take “no” for an answer and what he wants

he gets, even if it belongs to someone else or has been promised to another

person.

The villagers are held together not only by their poverty

but by their dreams. Andak’s dream is that he is living in a “big, beautiful

house beyond measure”. The mansion is so beautifully designed and enormous that

although Andak runs from one end of the mansion to the other end, he will never

be able to reach and meet its end. Likewise Andak dreams that his paddy fields

are as “wide as the ocean” but unfortunately he cannot harvest the rice. Tok

Aki, the voice of reason, warns them not to daydream but to work hard, for the

land is all that they have. But for Mak Andak dreams are all they have. They

have absolutely nothing. They can only dream, for by dreaming they can have

everything.

In an attempt to better his fortune, Andak decides to leave

the village and cease to be a paddy planter. Interviewed by Pujangga, he admits

that he has been chosen to work for the titled Tuanda who is rich and powerful

beyond measure. Before leaving for his new job, Tok Aki, Anjang and Mak Anjang advise Andak to always

do as he is told, to be good, to be aware that his knowledge is limited. Andak

is also reminded not to go against rules, not to challenge traditions, and as

always not to forget his daily prayers. He is cautioned not to try to be too

clever and always to do as he is told. Above all, he must always remember that

he is of the lower class. As such he must always behave. Such are the advice

and warnings that his parents and the village elders impress on him prior to

his leaving to go and work with the Tuanda.

Tuanda, on the other hand, is on a mission to empower his

social standing. He wants Pamanda to seek a suitable bride for his son. But his

son has no interest in the princesses from other lands or the great women with

class and status. Instead, all the son wants is Inah, the paddy planter’s

daughter. Since, his son is adamant, Tuanda agrees that his son shall wed Inah.

But Inah shall be reconstructed to fit into the new class she is entering into.

On Tuanda’s orders, Pamanda will get the best hairdresser, the best makeup

artist and the most renowned couturier to dress and transform Inah to become a

lady fit for his son. Inah shall also be taught all the social etiquette befitting

her new status. More importantly, she shall be taught the proper ways of

speaking and the correct pronunciations, for according to the Tuanda ‘The way

one speaks determines one’s class.’ The education and reconstruction of Inah

must be complete to enable her to be assimilated into Tuanda’s social class.

Before everything else though, Pamanda has to go and

officially ask for Inah’s hand. This must be properly done, to be

accompanied by a grand ceremony. Through

this social endeavor, the playwright shows how Anjang and Mak Anjang willingly

accept Tuanda’s request ignoring the fact that Andak loves Inah and that they

plan to get married. Both parents accept Inah’s fate

not only as a fait accompli but as something to their own social

advantage. It is Inah’s fortune and luck but it is Andak’s misfortune that Inah

is wanted by Tuanda for his own son. Her parents’ acquiescence to Tuanda’s demands so irked

Tok Aki who then reminds them of their promise to Andak. Tok Aki feels that

they should not blindly comply but that they must refuse the betrothal, of

which certainly Inah’s parents simply cannot or would not do so.

The

wedding preparations are planned and organized by many committees befitting a

nuptial of such a grand scale. The setting up of the various committees is to

cater, not only to local guests but also foreign guests and the foreign media.

The playwright’s sarcasm of such grandeur is obvious. The wedding festivities

itself will last for 44 days and 44 nights.

It is not surprising that although Inah’s parents are

invited to be part of the wedding festivities, they would not be able fit in

Tuanda’s grand social scheme of things. They themselves realize that they will

be such absolute social misfits amongst Tuanda’s many guests. Hence they prefer

to return to their village. Back where they belonged, they dream about Andak

who appears to them with his hands and feet bound as he tries to push a boulder

up a hill with his chest. Reminiscent of Camus’ Sisyphus, Andak’s task is a

hopeless, futile endeavor almost symptomatic of his leaving the village,

working for Tuanda to make a better future for him and Inah. All Andak’s plans and dreams become

annihilated when she marries Tuanda’s son. And the village continues to be

poverty stricken and the villagers suffer in the scorching heat.

Amidst the social havoc, the pining and waiting for Andak’s

return, a Pujangga comes to the village. He is writing a dissertation and has

chosen the village as his focus of study whereby he will research and study the

impact of development and changes on the social, cultural development of the

village. Pujangga concludes that the villagers suffer because of an uncaring

system. Pujangga is later elevated to become the Pujangga Negara who also

becomes Tuanda’s assistant.

Andak’s mission to ameliorate his poverty comes to naught

when he is caught by Petanda and is accused of committing a number of crimes.

These include making too much noise and speaking too loudly, thus, disturbing

Tuanda’s sleep; voyeuring on the Princess Inah and refusing to cooperate with

Petanda, the investigating officer. Andak is incessantly questioned,

emotionally tortured and is on the verge of giving it all up. But

psychologically, he is emotionally helped and boosted by Tok Aki who is always

shouting, urging and interjecting encouragement that he not give up, that he be

brave and that he fight his torturers. At the end Andak does

not die, he overcomes all the obstacles thrown in his path and he

succeeds. He lives only because he has been spurred by Tok Aki’s words of encouragement telling him to

fight for his rights and not to give up. But

Tok Aki does not live, he finally dies. The voice of reason, logic,

bravery and conscience is finally annihilated.

The play culminates with Tuanda’s lament that the earth

they inhabit is prosperous, the land fertile, the people happy and friendly,

but ironically in spite of all these, they are all destitute and death is

everywhere. In the end the sole inheritor of all his splendor is Inah, but as

Tuanda admits, her origins are lowly and she is really not a legitimate

inheritor of the land. The play ends with Andak shouting the fact that he has

not died, that he is still very much alive and physically present.

Unfortunately, no one can hear or even recognize him. Andak, who has traversed

both worlds, the worlds of the destitute paddy planters and the rich, powerful

world of Tuanda, has seen it all, has been punished and has suffered, and

although he comes back, he has become a stranger to the villagers for they do not

recognize him and does not acknowledge his presence or return. As such he is

not in a position to offer any help to them.

True to his concerns, Johan Jaaffar in this play again

posits a myriad of binaries: power-powerlessness, plenty-poverty, class-classlessness,

obedience-revolt, rich-poor, titled-untitled and always underlying these

binaries are oppositions and paradoxes. It is a paradox that the earth is

prosperous and the land fertile but the farmers are hungry and destitute.

In this play, the playwright has given an image of a land

where happiness and joy have disappeared and death abounds. To make it even

more bleak, Inah who has been reconstructed to become Princess Inah is found to

be not the legitimate, proper inheritor of all of Tuanda’s splendor. In the

final analysis, no matter how much reconstruction went into the remaking

of Inah, she is still from a lowly

class. She cannot become part of the ruling power with status, class and

position. Although she has been changed and transformed, she does not

legitimately belong to Tuanda’s class.

She remains, in spite of all the changes, in spite of her marriage ties,

in spite of being called “Princess

Inah” she remains manacled in her lower class position with her old mindset

unchanged.

4.KOTAKU OH KOTAKU/ MY CITY OH MY CITY

In this play, Johan

Jaaffar puts on centre stage

characters that are seldom put on stage in front of the curtain. Often these

characters are unseen, unwanted and when they happen to be seen they are

avoided or, they are looked down upon and frowned for having come out to share

a common space. These two characters are the Night Soil Collector and the

Sweeper.

The playwright sets the meeting of these two characters in

the Lake Garden a well-kept place full of trees, shrubs, flowering and

non-flowering plants which are created and encompassed within manicured lawns.

It is a place of tranquility, a garden right in the middle of the bustling city

of Kuala Lumpur. It is presented that when the Sweeper leaves after his job of

sweeping the city is completed, the Night Soil Collector would then come in to

do his job. They meet in the Lake Garden and in this confrontation they accost

each other by pointing out how each has no right to “pollute” the tranquility

and beauty of the Lake Garden by just being physically present there.

They are joined by the Prostitute who has made the Lake

Garden a place to ply her trade. All three clamour not only their right to be

there but also loudly proclaim the services that they do to the country. The Sweeper

who cleans the city of its rubbish proclaims that Kuala Lumpur will certainly

be buried with rubbish if the

likes of him do not do their duty of clearing the city

of its garbage and keeping the city clean. The Night Soil Collector brags that

if he does not collect and throw away what he claims to be man’s possession

which he most hates, namely his own excrement, the stinking smell will make

people feel disgusted and the

uncollected filth will become a health hazard. They both know that without

their services, the people of Kuala Lumpur will surely not be able to

live well and peacefully and that, eventually, they will all die.

Likewise the Prostitute proclaims her contributions to

society. Without her services, those who have come to need and greatly depend

on her, will become lost, disoriented and they will also not be able to

function properly. She provides her services to all, from important leaders

high up on the social rung, to the lowly Night Soil Collector and Sweeper if

they so need and desire her services.

She can even render her service right there and then, in the Lake

Garden, just to please her clients, reduce their stress, make them whole and

functional again.

Still no matter how great their services and how

indispensable they all are, they are just denizens of the city who are frowned

upon and their physical presence in the

Lake Garden are not wanted. Their very

presence will cause discomfort to those who frequent the place. Both the Night

Soil Collector and the Sweeper will make the people who are enjoying the

sights, smells, beauty and tranquility of the Lake Garden leave the place, for

they will certainly be unable to stand the foul stench emanating from these two

beings. Likewise the likes of them will also jar the peaceful, beautiful milieu

with their dirty and stinking presence. All of these traits can be seen from

the confrontation between these two characters as they laud their own

contributions and significance to the city and its inhabitants even as they

both point a finger at each other’s disgusting, foul smelling and demeaning

presence. They are just not welcome in the serene calmness of the gardens. This

is best exemplified when the young couple sitting on the bench, who are just

enjoying the fresh air and each other’s presence, are disturbed by the foul

stench of the Night Soil Collector and Sweeper. These two has just been denied

their most basic right, namely to just be there in the Lake Garden like the

other city dwellers could.

Hence Jebat, the modern day version of this legendary

figure appears on the scene to fight for the rights of people, in the likes

of the Night Soil Collector, Sweeper

and Prostitute. Jebat’s presence on stage is not only a spoof of the classical

Malay (anti) hero but also a representation of the trajectory that these

people, frowned and looked down upon,

unwanted, yet whose services are crucial, are also beings who have the right to

be at the Lake Garden. It is also to point out the irony of opposing needs and

social abhorrence.

Sweeper’s family

living in the village is proud

that a village son works in the city of Kuala Lumpur. But Sweeper himself knows

and tells his family that the

people of Kuala

Lumpur look down on him; they find his job demeaning

and they prefer not to have anything or

any contact with him. It is a hilarious scene to see Sweeper describing the

bustling city of Kuala Lumpur to his village folks. Sweeper’s description of

the city’s sky scrapers can only elicit an imagined analogy of these buildings

from the mother who can only compare them to the various tall trees in the

village that she knows. Sweeper’s wife concludes that K. Lites (which is pronounced as Kay El Lites,

referring to the inhabitants/city dwellers of the capital city of Kuala Lumpur)

must be very good, agile and competent

climbers to be daily climbing up and down these very tall buildings. Sweeper

corrects her (mis)conceptions by telling her that there is no need for K. Lites

to be agile for they do not have to physically climb these high buildings. He

tells her that these sky scrapers come

equipped with lifts/elevators and explains to her how this mechanism

functions.

Looked down

upon and humiliated,

although the services they provide are so crucial to a city’s survival,

the sweepers, night soil collectors and prostitutes unite and decide to go on

strike thus effectively denying the city of their crucial services. Imagine a

city buried deep in garbage, its filth not collected, its stinking excrement

turning putrid and the overwhelming disgust at the foul smell not to mention

the proliferation of diseases. The city leaders become cranky and are not able

to function and do their jobs well because the Prostitutes have also gone on

strike. By withholding their services

and going on strike, the prostitutes effectively deny the city dwellers, or at

least those who rely very much on their services, their much needed stress

relieving, enjoyment source providers.

The

result of the strike is the demolition of the city’s health, beauty and natural,

social upkeep. Because of the widespread disease, Jebat, the people’s leader,

fighter for their rights, champion of

their needs, also succumbs to whatever diseases that has inundated the

city. Jebat’s death is a wakeup call to those on strike who decide to end their strike and get

on with their jobs of cleaning the city and getting it back to its normal,

pre-strike state. The play ends with a return to normality and a cementing of

the status quo.

In “My City Oh My City”, the playwright deliberately

nullifies the main stereotyped images of creative writers and the description

of women. The young couple, simply named Young Man and Young Woman, epitomizes

a loving pair out on a date. In his construction of this social episode, the

playwright makes the Young Woman refuses to be described in the cliché manner

of equating her to the moon, which she tells her beloved is really not beautiful either, for

the moon is full of huge pock marks. His

sweet words to her are all annihilated when she asks him whether he has borrowed these words from some

romantic poet like UsmanAwang! She does

now want him to be a poet either for he will then be describing her in a poetic

finds unappealing.

In this play,

Johan takes a look at stereotype

images, of poets and artists by making fun of the language peculiarly used by

poets and the etchings, lines, abstract art of the artists/painters.

Concomitant with this literary concern, the dramatist has given the characters

of the Great Poet and the Great Writer to represent the

creative, literary endeavors of his dramatic spectrum. The nation’s foremost

poet, simply named Great Poet, seeks inspiration everywhere and in

everything: the stench of drains, leeches, pus and the gloomy, squalid

villagers on the

fringes of the city. The poets are mocked at in this play when they seem to think

that they do not need to have education to become good

poets, all they

need are to have feelings,

sentiments, visions and illusions. Above all, they need to be creative. It is for this reason

that the Great Writer only needs to stand and stare, and willing inspiration to

come to him so that he can produce his great literary masterpiece.

“My City Oh My City” is a deliberate reconstruction of

society from the Night Soil Collector and Sweeper’s perspective to ensure the

sustenance of the health and cleanliness of the city. Without these lowly

subaltern denizens performing their jobs, the

city and its

inhabitants will be ravaged by diseases and like Jebat , they will surely die. The play is a

wake up call to appreciate these denizens. More importantly, it is to mock the

stereotype image and perceptions of K. Lites.

5. PASRAH / SURRENDER

“Pasrah” is a short one act play peopled by characters who

are simply named One, Two, Three,

Four and a Stranger. It is a play where absolute

despair seems to be the subterranean leitmotif

and the characters

comprising of the four friends only talk about death, loyalty and love which have to cease to exist; they

also reminisce about greenery which is now lost, hence, non-existent and about

emptiness. For these friends, death is a utopia to look forward to. They are

discussing about a

coffin which they have been guarding for seven thousand years and are

beginning to realize the futility of their work and existence.

Typical of a profoundly nihilistic play, the friends

realize that after enslaving

themselves for the

past seven thousand years, the

only thing they have discovered is that

all they could get for their enslavement and efforts of doing whatever

they had been asked to do was torture, boredom, and hatred.

They even have to sacrifice the pleasure of having

women and children around, for these have all become extinct.

Throughout their lives, they have been compelled to be

loyal and to do as they were told. Thus it is that they now tell themselves to

relinquish everything, to surrender their fates

and and all that they have been

doing. They want to return to a state of nothingness.

Like in his other plays, Johan could not resist putting a

character, Two, who is the creative persona in the play. Two has written a poem

which had taken him seven thousand years to write and it certainly is the best

poem ever written. He is proud of his creative, literary input. As in his other

plays, like in “My City Oh My City” for instance, Johan takes a satirical look

at creative writers, especially poets. The

playwright seems to take issues

with poets perhaps in an effort to urge them to better and greater efforts. Or

perhaps he is just mocking their poetic efforts and endeavors.

“Surrender”

is the playwright’s tour-de-force, full of nihilistic despair and

existentialist angst where the character, One, says “a tragedy is an everyday

entertainment”. It almost seems that in this play, all the characters are bent

on a mission whereby all that they are concerned about is to extol their

despairs, regrets and the futility of

existence.

6. ASIAH SAMIAH

This is an epic play about love, lust and power which

engulfs the entire life of Samiah from when she was a child, to her becoming a

young woman and eventually to becoming an old, mad woman. Johan has taken a

female character and made her almost like a whirling, centrifugal and

centripetal power. The play presents numerous issues of emotions, status, love,

man’s gregarious and lustful nature. To complement the picture, perhaps, the

play also delineates the innate weaknesses of women who finally must physically

succumb to men. But, like the phoenix she rises yet again to live independently

and even happily in her own mad, insane world. In this mad world, unknowingly

and unconsciously, she will still have her revenge as she continues to disturb

and disrupt the sane lives around her who are in their “sane”, “normal” world,

outside of her mad, demonical sphere. The ironic truth is, it is Asiah Samiah’s

very madness that becomes her saving point. It is the one thing that keeps her

alive. For in this raving mad world, Asiah Samiah finds comfort and solace as

she continues to live in a past long gone or destroyed, at a time then when she

did not know hardship, emotional destruction or love denied and betrayed.

As a young, only child, Asiah Samiah was the doted upon,

beloved daughter of her parents, Tuan Setiawan Tanjung and Puan Suari Alimin.

Asiah Samiah fell in love with her childhood friend, Anas Samanda, a poor,

romantic idealist, who although he suffered for his principles and beliefs,

still managed to woo and win Asiah Samiah’s love. But unlike the romantic tales

of yore, where the beloved couple live happily ever after, Asiah Samiah’s and

Anas Samanda’s love for each other came to nothing; in fact it was cruelly

destroyed by Misa Sagaraga who with his wealth, power, status, greed and lust

denied Asiah Samiah her world of romantic-ideal love with Anas. Her marriage to

Misa Sagaraga resulted in the birth of Laila Anurisah. But Asiah Samiah made a

rather hasty decision when she left the house, her baby and her husband. Asiah

Samiah’s actions so shamed her husband who then decided to sever all ties with

the baby by simply having her thrown away. But the baby was saved by Siti Bunirah. Laila Anurisah grew up to become not

only a very lovely young lady but also a pious one. Her piety and religiosity is symbolized by

the fact that her head is so neatly covered by a scarf. Her headgear becomes an

important signifier of her determination, courage, independent spirit, and

above all her religious belief and commitment, all of which had helped her

throughout her ordeal.

In this panoramic, epic drama of love where lust, power,

ideology and idealism are always in ever changing, contrapuntal relationships, the one steadfast, loyal,

sane certainty is only Marga, who, from the time he was young until he is old

continues to love Asiah Samiah. This unreciprocated love does not prevent Marga

from doing all he can do to take care of Laila Anurisah when she was a very

small child. He even took her to see Anas Samanda to tell him about Asiah

Samiah’s daughter. Instead of loving or even liking the child, for she is after

all Asiah Samiah’s daughter, Anas Samanda

chooses to hate the child on sight. Asked to guess her name, Anas,

correctly knows the child’s name, much to Marga’s surprise. But as Anas Samanda

explains that was the name chosen by Asiah should they have a child of their

own. For Anas Samanda, the child, Laila Anurisah, has become

a signifier of something hated, unwanted, of the destruction of his love

for Asiah Samiah. Therefore, he does not want to have anything to do with her.

He does not want to see her as being part of

Asiah Samiah, the woman he once loved.

For

her own father, Misa Sagaraga, Laila

Anurisah symbolizes the shame heaped on him by his wife, especially when she

decided to leave him and abandon the child she had with him. This unwanted, abhorred

child in turn becomes a symbol of his hatred, animosity and shame. He callously

decides to just throw her away. For Marga, Laila Anurisah is something

unattainable, a might have been, a reminder of love unrequited, hence a symbol

of his unreciprocated love for Asiah Samiah.

But if the love had been requited and reciprocated, it would have been

something to be loved, adored and cherished.

Marga’s love for Asiah Samiah is exhibited in many ways.

Even when she was a child he was already reading and telling her romantic

stories. From the time Asiah Samiah became a young adult, in all her beauty,

although her behavior was callous, Marga loves Asiah, even when later in life,

she was ostracized by society. Every day at dusk he sits on a bench waiting for

the mad Asiah to appear and sing her song of woe and fear. Marga knows that in

her mad condition Asiah Samiah is cocooned by her insanity from further torment

and torture. She continues to live in her own dream world remembering only her

love for Anas Samanda and seeing her abandoned Laila Anurisah as symbol and

proof of her love for Anas Samanda.

It is also because of his profound love for

Asiah Samiah that Marga proclaims to her daughter, who has come to seek

confirmation about her mother’s existence, that her mother has indeed

died. MargaTua’s lie that Asiah has died

is to safe both mother and daughter. He does not want to tell Laila Anurisah

that her mother is still alive or that she has become a stark, raving mad,

insane woman. At the same time, MargaTua does not want the mad Asiah Samiah to

see her daughter whom she has abandoned come to haunt her. Thus it is that

Marga Tua convincingly tells Laila Anurisah, who is now 24 years old, that

“…your mother, Asiah Samiah, is dead,”

To a certain extent MargaTua’s statement is not wrong, for

definitely to those who are normal and sane, the mad Asiah Samiah no longer

exists. She is no longer herself. It is almost as if she has really died, lost

to the “real,” world. It is only Marga Tua who continues to love her, hence his

constant, everyday ritualistic vigil of sitting on the bench at twilight, to

wait for the raving mad Asiah Samiah to approach him.

The play is not only a drama of love lost, won, to be

forever lost yet again, or to exist but under such horrible, painful

conditions, as a reminder of something unachievable; it is also about wealth,

power, status versus principles and ideologies. It is a play delving into

questions of dignity, pride, self-worth and moral values. Anas Samanda is the

poor, idealistic man who has grandiose notions of principles, rights, ideology

and dignity. In contradistinction to him is Misa Sagaraga who is wealthy beyond

measure and who will not let anything or anyone stand between what he wants.

Marga Tua really is the outsider who has learned from the bitter experience of

his past. He remembers clearly the

things which happened to his family

which has made him become the sort of man that he is now. Because of all

the sufferings, shame and humiliation which he and his family endured, he is

now be able to live without the ideology which had so fired Anas Samanda’s

whole life. Marga Tua learned from seeing how his father was dragged away from

his home like a criminal and how his father was then imprisoned, humiliated and

tortured. Marga Tua realized a long time ago that, as he tells Anas, “we’re

just too small to change the world.” But it is not a lesson that Anas Samanda

wants to or can believe in or abide by. So it is that Anas sacrifices his love

and he dies fighting for his principles of justice, dignity and equality!

Issues

and dramatic techniques

This epic love story is told in a language that is simple,

easy to understand, in the swaying, rhythmic, linguistic movements which are

poetic, although empowered by a dramatic technique that is tight, taught with

emotions, struggles, ideologies, principles, sacrifices and sufferings. Johan

Jaaffar in an ordinary casual manner, has spun a soothsayer’s tale, with

several songs forming a leitmotif to the plays development, progression and

impact. Throughout Asiah Samiah, Marga Tua and even Laila Anurisah sing parts

of the ligal, ligal song as a contrapuntal juxtaposition to the interweaving

betwixt emotions, power/powerlessness, ideology, love, and (in)sanity. The

playwright has drawn out a dramatic tale which affects the heart, provokes the

mind and simultaneously jars and makes ordinary life and living topsy turvy.

The play seems superficially devoid of loud emotions,

exemplifying instead a simple tale of love lost or never won, but within this

continuum, the dramatist posits the growing and becoming old of Asiah Samiah,

Marga and even Laila Anurisah. Hence in the play Asiah Samiah is known as Asiah

Samiah Muda (the Young Asiah Samiah) and Asiah Samiah Tua (the Old Asiah

Samiah). Likewise there is Marga Muda and MargaTua and we are told about the

abandoned baby, Laila Anurisah, and we see her when she is twenty four years

old looking to find her mother.

The dramatic narratology is interestingly developed through

a variety of techniques by using simple dialogues, recriminations,

lamentations, oratorical and legal speeches as well as songs. If Asiah Samiah

is both the centrifugal and antipodal magnet/power, the songs she sings are

both the leitmotif and doppelganger to the mad intricacies of the old,

self-abandoned Asiah Samiah.

The play is also about the nostalgia, of especially, Marga

Tua, as he reminisces about his father’s fate, his family’s misfortune and

their subsequent social ostracism. But he also remembers his love for Asiah Samiah

and recalls that it has always been, in fact, unrequited love from the very

beginning. Throughout Asiah Samiah has eyes, ears and heart only for Anas

Samanda. Marga Tua also recollects how Asiah Samiah has been rather callous, in

protecting and projecting her love for Anas Samanda. She is always seeking help

and confessing to Marga about her feelings for Anas. In spite of it all, Marga

continues to love Asiah Samiah. If it is a tale of love and loyalty, it must be

that of Marga’s love for Asiah Samiah symbolized by his sitting on his bench at

twilight to wait for the mad, Asiah Samiah to come and reminisce about her past

and sing her leitmotif songs. And he does this every day, without fail. In fact

the measure of Marga’s love for Asiah Samiah can be seen in the fact that it is

he who takes care of Laila Anurisah, even taking her to see Anas Samanda hoping

that in Laila Anurisah, Anas will be able to see and recall the love that he

once had for Asiah Samiah. The child is supposed to be the symbol of their

ruptured love but instead of remembering his love, Anas chooses instead to see

Laila Anurisah as a symbol of

destruction, betrayal and hence of his unfulfilled love.

Therein

lies the difference between Marga’s and Anas’ love for Asiah. Marga will take

care of the child not only because she is just an innocent baby but because he

loves her mother so. Misa Sagaraga, the other male, in this triangular

relationship, also “loves” Asiah Samiah but in his case it is more of making

sure that he gets what he wants because he has power, status and wealth.

Although Asiah Samiah does not like him, still on their wedding night she

succumbs to physical pleasure, much to her own disgust. Misa Sagaraga’s love,

like Anas’ love for Asiah Samiah is transient and conditional. When Asiah

Samiah decides to leave husband and child, Misa Sagaraga’s lust/love turns to

hatred which he takes out on the baby.

Such

is the stormy love story of Asiah Samiah and the two men in her life. Intertwined within this triangular love story

is the fact that Marga Tua becomes an outsider/ observer of the love song

between Anas Samanda and Asiah Samiah. Marga Tua only remembers and recalls a

past nostalgia. But he is not just any ordinary observer for he becomes also a

participant, central, crucial and very emotionally involved. It is this

centre-periphery dichotomy that becomes yet another dramatic device chosen by

the playwright. The other love is the normal parent love and love as seen in

the responsibility of taking care of Asiah Samiah as a child.

Besides the love-hatred story, the play also reveals other

binary oppositions, especially in the ideological warfare between Anas and

Marga’s father. Marga’s father was imprisoned because he dared to fight for his

principles and defended his right to the piece of land which had been his all

this while. Tortured and humiliated, Marga’s father refused to back down. His

principles did not help, but instead hurt his own family although it benefited his neighbours for they did not have to give up their land since he had opposed

it on their behalf! The fight, struggle and ideology became magnified in the

son. Anas Samanda was imprisoned because he wanted to fight for a bigger cause:

to change the minds and ethos of the masses.

And

like his father, he too did not succeed. This play is inundated with opposing

themes of madness and lucidity (real or imagined), of love and lust, of forced

compulsion and meek submission. These contrapuntal juxtapositions and binaries

in turn become the foundation to exemplify social concerns and ethical choices,

tradition and modernity, unimaginable wealth which can enable the rich to

purchase exorbitantly branded foreign goods whilst the destitute poor have to

struggle daily to just eke out a living. Herein lies the social trajectory of

this play.

Although the play deceptively uses simple everyday

language, it is so crafted to become ironically complex and complicated. This

in itself is yet another binary tool deeply exploited by the playwright. The

complexity can be seen from the differing layered shifts in time, the

progression from young to old, the flashbacks, the linear development of

thematic present-past-and even past past. Even the dialogues between Asiah

Samiah Tua and her parents are deliberately contradicted at a time when she was

young. This is further showcased when she interjected their dialogues about her

heart as can be seen, for example, in Act. 6.

For this writer, Asiah

Samiah epitomizes the deep structured revelations of a very craft conscious

playwright who also scathingly criticizes the social milieu of his society. The

playwright mocks brand conscious members of society who cannot even pronounce

the brands they are buying and using as can be discerned from Misa Sagaraga’s

dialogues in Act. 7. This is further illustrated in the endeavors undertaken by

Misa Sagaraga as he goes about reconstructing Asiah Samiah in the image of his

liking by having her clothed in expensive designer labels, made up by

professional artistes and ensuring that she uses only branded goods. He wants

to transform her into some ideal woman he envisions in his imagination, which

his wealth, power and position can make into reality.

In this play, the dramatist also takes an autobiographical

jibe by having Marga Tua’s journalist friend leave the media world for reasons

best left alone, as was once done by the dramatist himself.

Asiah Samiah is

Johan Jaaffar’s tour-de-force as he encompasses social concerns, grapples with

class, conflicts and enumerates power-wealth-status within a polar binary of

weakness-destitution and classlessness. By imbibing these issues the playwright

once again reveals his empowered stance and dramatic craft for a genre which he

has abandoned for a rather long while. It is almost as if with this play, the

playwright returns to the world of theatre with a vengeance. Hopefully he will

utilize his dramatic craft, social concerns to further enhance modern Malay

theatre.

7. PEMAIN / THE PLAYER

Johan Jaaffar has rightly categorized this piece of

creative writing as a novelet/ drama/ short story and it certainly can be

analyzed as either of these creative forms. In this anthology, it is seen as a

piece of dramatic literature, especially as a subgenre of monodrama which only

serves to prove that long before this genre became popular in Malaysia, Johan

Jaaffar had already been an avant-gardist. The play can be read as a long

monologue, parts of which are the interiorization of one person’s personal angst in a world which is cruel,

uncertain, indeterminate. This play is constructed as always along opposite

binaries of leader-led, power-powerlessness, the haves against the have-nots,

love-lovelessness, certainty-uncertainty, hope-despair, reality-illusion,

truth-lies amongst other.

The central character is the narrator/ old philosopher

whose Joyce’s Molly like monologue goes on many trajectories as he thinks

philosophically about the self, questioning himself about his own innate self

as perceived by himself and by others. He is also on an existentialist quest of

first trying to figure out what is and what is not, what is right and what is

wrong, what is present and what is absent. These positionings seem almost like

a philosophical treatise on the various meanings of existence, beliefs,

perceptions, relationships and power. It also can be read as a political

treatise of individual, personal freedom as opposed to a collective

responsibility egged on by leaders or those who have been empowered with authority

to impose law and order. The play can also be represented as a social

construction and Foucauldian

deconstruction of power, punishment and acceptance. Above all the play can be

read as an existentialist treatise, where the most profound question haunting

mankind is who is he really and what does it mean to be him. Other related

philosophical demands include the continuum of truths or non-truths, whole

truths, when is it true or why is it true or even why is it not true. Truths,

like other metaphysical questions, are always subjected to presentations,

perceptions, reconstructions and reevaluations.

Loyalty is also a social construct and contract to be

fulfilled only for a length of term and then discarded when it is no longer

useful or the person who is being loyal has become a liability, hence useless.

The philosopher cites the story of the dog and its loyalty to its owner. The

dog which had served its master well was simply thrown away when it was no

longer useful. But the dog can still find its way back to its former owner’s

house and although it is no longer wanted or welcomed in the house, in fact the

children’s owner simply chased it away, the dog continues to sniffle around the

front gate and rummages for food in the garbage bins.

In this tale, the dog’s loyalty is poorly rewarded by its

owner. The thrust of this story is that of power relationships, for the one who

has power can not only do as they like but can be callous and ungrateful.

Loyalty, like friendship, is placed on a trajectory where its value is

constructed by others and dependent on power and usefulness as perceived by

those with power.

The play also (re)views man-woman relationships as

exemplified by the old philosopher/ narrator/ the person who has been in and

out of prison and Yie, she, who is now a management expert. This is not

surprising for Yie has been taught management theories by professors who

themselves have been trained in the best universities! Like in some of his

other plays, the playwright cannot resist re-presenting the peculiar world of

academia and also of poets. In this play, the old “philosopher”, the I/the

narrator is also a poet. He compares himself to the renowned Rendra as he

writes a poem on “Death”. He takes pride in the fact that he will be remembered

for writing a poem using only one word, that one word being “Death”. He might

even win Malaysia’s Literary Award for using only the word “death” the most

number of times in one poem. Johan seems to be gleefully re-presenting images

of academicians and poets in this monodrama, even as he takes a jibe at

literary awards given to writers. He is both mocking the recipient of such

awards, namely the writers and the organization/institutions giving those

awards.

The play also takes a critical stance at the roles of television,

books and magazines, the print and other forms of media for belittling ones’

intellect. In short, the play makes comments on the inadequacies of the media

in (not) fulfilling its social, intellectual and creative functions of serving

the larger societal concerns.

Intelligence is an issue crucial and central to this

monologue/ monodrama. Likewise is mental stability or the lack thereof and how

this is perceived in a stereotyped manner. The play posits that mental

stability is a social creation, constructed and normally perceived without much

debate by others, whoever those others are. But the reality is, according to

the “I” of the play, is the fact that the inventions, innovations and creations

which have impacted society have been done by people who are not stable.

[In]stability actually creates creativity.

Yie is also presented as a workaholic who is also very well

disciplined. Each morning she will go to work accompanied by the 12 written

things on her list which she needs to do for the day. At the end of the day,

Yie will make sure that all the 12 items she has on her list would have

disappeared.

Through the lenses of the narrator/ philosopher whose every

movement and action are recorded, one must ascertain a broad range of concerns

including the continuum of power, laws and rights. The old philosopher reminds

the reader of Marga Tua’s father in “Asiah Samiah” for the philosopher in this

play reminisced about what happened to him when he fought for his rights. The

philosopher re-voices Marga Tua’s concern/ dilemma that the meaning of freedom

is never understood until that freedom is denied and lost.

Besides freedom, the right to do, speak, think, act/behave,

own or believe in, the play also focuses on personal, familial and social

relationships. The relationships are seen in how the narrator constructs his

relationship with Yie, the management expert. For her, no matter how highly

educated she has been, on a personal, man-woman front, Yie still succumbs to

stereotype, images whereby she sees herself as a damsel in distress and dreams

and believes that a knight in shining armor will come and save her. In her

dreams, she imagines that she is tied to a tree but she will certainly be

rescued by her knight.

The narrator, the I’s many philosophical roles and

functions in society are constructions formed in his recalling of past events

within the spectrum of his current dilemma whereby he is an outcast

of society as viewed, interpreted and legally enforced by those members of

society who have the power to do so. The “I” of this Jocyean Molly Bloomlike

existential ramblings full of angst is

finally seen as the myriad facets of many persons. He is Yie’s lover, he is

also his own sister, Amie’s, brother, just as he also describes himself as an

old philosopher and a poet. Others also perceive him to be a traitor to his own

race for he has betrayed them. He is seen as the enemy of the majority and that

he is not being naturalistic. He acknowledges all that they say and perceive of

him for when all is said and done, he alone knows what he has experienced and

undergone. He certainly knows that the price of dignity is excruciatingly

cheap.

For all the sufferings that the “I” of the play has to

endure, for the severance of familial, social, personal ties, for the freedom

he fought for, for his rights that he so championed and lost, for his beliefs,

his sufferings, his endurance, his strengths and his weakness, “I” finally

realizes that really and truly he does not know anything, anymore, and that

certainly he has no answers, no truths to abide by, no absolutes to believe in.

He is almost the magnification of an existentialist philosophy of absolute

despair interspersed ironically with momentary flashes of hopes, dreams and

abilities.

Written as a treatise of life by an I/ philosopher/

narrator/ crusader/ lover/ brother/ son, the play drama is aptly titled “The

Player” signifying the many roles, masks, faces, fronts that one constructs or

are constructed by others simply by being an inhabitant of society.

In the beginning, this mono-drama or a long monologue is

reminiscent of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s the little prince, whose

interjections and self-deprecation's seem to summon receptions and responses

from readers to take a deeper look and make a deeper reading of the text for

these interjections are deliberately done almost in a Brechtian Verfremdungs effect.

“The Player” serves to put mono-drama on an important

forefront, capitulating the many, varied possibilities of dramatic

re-presentations and theatrical conceptions. This is yet another of Johan’s

contribution to the drama world done at a time before mono-dramas became a

favourite (re)presentation on the Malaysian theatre scene.

Conclusion

The seven plays translated for this publication includes

Johan’s renowned trilogy of “Angin Kering”/Dry Wind, “Dia’/Someone and “Sang Puteri”/The Princess.

This group of plays including “Kotaku Oh Kotaku”/My City Oh My City and

“Pasrah”/Surrender has positioned Johan Jaaffar within the absurd-abstract-surrealist

experimental plays so lauded in the decade of the 1970’s. More than the epoch

making experimental newness of the plays, they are important as social

critiques and treatises of paradoxes contained in all its myriad possibilities

in society.

The poster for Sang Puteri staged at Pangging Eksperimen UM on 20th & 21st October 1979

These paradoxes seem to haunt Johan as he grapples with

delineating, presenting and postulating to his readers/audiences the paradox of

want amidst plenty, the paradox of love and lust, the paradox of greed and

selflessness, and throughout, almost always, in one form or another, in voices

loudly heard or deafeningly silenced, the paradox of poverty and deprivation

amidst that of plenty and abundance.

He continues and substantiates these concerns in his latest

play, the award winning Asiah Samiah.

It is interesting to note that through the meanderings and morphological

metamorphosis of Asiah Samiah, Johan

once again embarks not only on his trajectories of paradoxes but imbibes within

this play metaphorical and existential elements of alienation, despair and

angst. “Asiah Samiah” beckons readers, audiences, critics, academia into seeing

Johan Jaaffar, the ever present playwright, under new lights and

considerations. The play’s thematic stances, the songs which become leitmotifs

not only for the central characters but for the overall reflections and

refractions of the play serves only to highlight Johan Jaaffar as one of

Malaysia’s paramount playwright. This has been further proven by Pemain/The Player read within the

epistemological context of a scatological dialogue almost irreverent in its

critique of society and societal concerns. These are then pivoted within

individual binaries of hope-despair, light-darkness, presence-absence, love

won-love lost. The play also shows how in the forefront Johan has been with

developing the different forms and sub-genres of writing plays.

One of the plays directed by Johan